Clip it or stick it? How to wear this season’s patches

Anyone who attends an event, from an exhibition to a company get-together, will know the dilemma of name badges: clip-on or sticky label? How and where to place them? The virtues of both are hotly debated, but in medical applications, adhesive patches could revolutionise diabetes treatment, says Caroline

A recent report by IDTechEx Research shows the market for electronic skin patches is strong and set to accelerate over the next 10 years.

Electronic skin patches are made up of different adhesive substrates, according to application and use sensors, actuators to communicate and process data from the body. They are, says James Hayward, senior technology analyst, IDTechEx, “one of the most direct means to augment the user with technology”. In medical applications they have advantages over monitors, however small and light, that can be clipped or strapped on to the patient. They can be applied directly to an area of interest, for example to monitor the heart, or the head to monitor concussion or activity. The format provides a consistent electrical interface for reliable sensor readings. They may also be part of a system delivering medical directly using microneedles for diabetes treatment for example.

Research published in Electronic Skin Patches 2018 – 20128 shows that the commercialisation of the flexible, wearable electronics patches is expected to reach over $10 billion per year by 2023 and nearly $15 billion by 2028. The market is still quite young; although forecasts were that patches would account for nearly a third (30 per cent) of the healthcare, sports and fitness market by 2020.

The direct application means electronic skin patches are commonly used in

cardiovascular monitoring and diabetes management. As manufacturing techniques evolve, mobile cardiac telemetry (MCT) devices, Holter and cardiac event monitors can be all be reduced to electronic skin patches. They allow the patient a certain amount of mobility while still collecting data. Patients can be at home or moving around to free up hospital beds as well as make life more comfortable for the patient.

In diabetes management, manufacturers are developing continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) devices to build up a longer term picture of blood glucose levels. Other R & D is investigating using insulin pumps as well as CGM devices as skin patches.

The nature of the sensors and actuators and accompanying electronics can ‘bulk’ up the skin patches; a lot of R&D effort is being directed at flexible, stretchable substrates and conformal electronic components.

Painless glucose monitoring

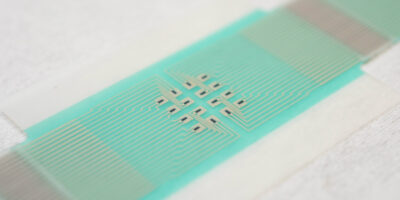

Measuring blood glucose levels without taking blood samples would free up a lot of diabetes sufferers. An adhesive patch can be used to measure levels by drawing glucose from fluid between cells across hair follicles. An array of miniature sensors, using a small electric current draws out the glucose to be measured, without piercing the skin (Figure 1). Readings can be taken every 10 to 15 minutes, over a period of several hours.

Each sensor of the array can operate on a small area over an individual hair follicle to reduce variability in glucose extraction. It also increases the accuracy of the measurements, removing the need for a blood sample.

A research team at the University of Bath, published a study in Nature Nanotechnology, and believes that the concept can be refined to become a low-cost, wearable sensor, sending regular glucose measurements to the wearer’s phone or smartwatch wirelessly, with alerts if glucose levels reach a level where action is needed.

Figure 1: The array of sensors on a skin patch for glucose monitoring was developed by scientists from the departments of physics, pharmacy & pharmacology, and chemistry at the University of Bath. (Picture: University of Bath)

Testing the patch on diabetic human patients, and on healthy human volunteers, the patch was able to track blood sugar variations throughout the day.

Smart patches

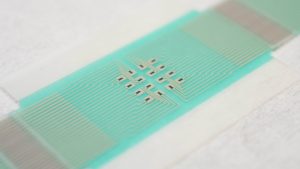

A team at Seoul National University, South Korea, has taken this a step further, with monitoring and medication without intervention. A team developed a prototype patch that can analyse the patient’s sweat to sense glucose levels (Figure 2), eliminating taking blood samples, and to control glucose levels by injecting medication via micro-needles in the graphene-based patch. Each needle is coated with medication and pierce the skin, to painlessly Professor Kim Dae-Hyeong explained that the graphene-based batch senses when glucose levels are higher than normal, a tiny heating element switches on to dissolve the medication coating the micro-needles to release the dose into the body.

Figure 2: Diagnosis and treatment in one skin patch is the challenge for the Seoul National University research team. (Picture: Seoul National University)

The prototype is promising, allowing patients to monitor and manage their condition without discomfort. Lowering the cost of production and refining a way to deliver enough medication to treat humans (the prototype was tested on mice) are the next hurdles before full a commercial offering can be feasible.

Diabetes UK has also reported on such a smart patch and the work of scientists at Swansea University to develop suitable micro-needles.

It describes a skin patch that has an array of 0.7mm, silicon-based, hollow needles which penetrate the top layer of skin (where there are no nerve cells or blood vessels) to deliver the insulin painlessly.

The monitoring system would be linked to a smartphone and inform the user when insulin needs to be delivered.

Within two years, scientists at Swansea hope to manufacture microneedles within two years. Challenges to be overcome are to develop a hollow needle with a sharp tip at this small scale, and within a reasonable price point if the patch has to be replaced each day.