Editors Blog – Picking up the threads of body armour

Caroline Hayes looks at some research projects for bulletproof clothing for the military combining traditional methods and new fibres

While working as a chemist in the DuPont laboratory, Stephanie Kwolek created Kevlar, a fibre that is five times stronger than steel but lighter than fibreglass. She had seen how polyamide molecules form a strong liquid crystalline polymer which she spun into a fibre. The synthetic fibre is also heat-resistant. It was used initially for steel in vehicles’ racing tyres. As development continued, the extremely strong fibre was woven into a fabric and used in bullet proof vests.

A bulletproof pattern

Since the 1970s, the manufacture of bulletproof clothing has relied on the same processes. Kevlar is one of the main raw materials, explained Scott Burton of Body Armor News, together with Dyneema, made from a polyethylene base, which is manufactured by a gel-spinning process that makes it soft as well as extremely strong.

The fibre is woven into yarn, which is then woven into a sheet of textile material, used to make bulletproof panels for vests.

This fabric is used just like any other cloth for garments, i.e. patterns and industrial cutting machines cut multiple layers of the fabric to shape and stitched together to create panels. The material is encased in a protective envelope, continues Burton, which can be heat-sealed to protect it from water ingress and humidity. The sealed panels are fitted into a ballistic carrier which has pockets designed to hold the panels against the wearer’s body.

Updating the yarn

Although Kevlar has served for over 40 years, researchers at Rice University, in Houston, Texas, USA and Wollongong University in New South Wales, Australia, are looking at how graphene could be used in modern warfare garments.

Experiments at Rice University showed that graphene is 10 times better than steel at absorbing the energy of a micro bullet traveling at supersonic speed.

Industrial fibres, such as Kevlar, Dyneema or Twaron stop bullets from penetrating the material’s surface. They also absorb the impact of the bullet. These have undoubtedly saved many lives but there are still injuries sustained, from severe bruising to damage to vital organs because the force from the bullet is still felt by the wearer.

The researchers fired microscopic projectiles at multi-layer graphene sheets and, with the use of high speed cameras, captured images of the graphene acting like a stretching membrane, distributing the bullets’ energy over a large area, literally softening the blow. The tensile strength of graphene has been well documented, but this research shows its can be elastic, stiff and strong all at the same time.

These characteristics could be used in body armour, as well as other military applications such as aerospace shielding, reports the team.

In another project, at the University of Wollogong, researchers have developed a graphene composite material which they say is stronger than spider’s silk and Kevlar.

The graphene composite was fabricated using a wet-spinning method to produce a yarn that is strong and lightweight for reinforcing material.

Further research is being done on the use of nanomaterials, such as carbon nanotubes and quantum dots, to find bulletproof material that can be scaled up for cost-effective mass productions.

Material choices

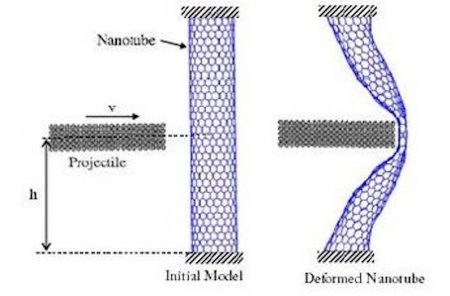

Cylindrical carbon nanotubes in a beehive-shaped structure have demonstrated great strength when hit by a projectile. Research at Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania, USA tested nanotubes with projectiles. When capped at each end and linked, the nano fibres were reported to be hundreds of times stronger than steel. Figure 2 shows a carbon nanotube subjected to ballistic impact.

Figure 2: a carbon nanotube (left) and its maximum energy absorption on impact (right). Image from Dickinson College

The carbon nanotubes are also light, flexible, strong, and thermally-stable. When these nanotubes are woven together in a lightweight material which sits between the lining of a bulletproof vest, it can absorb the energy from the force of a bullet, further safeguarding the wearer from ‘incidental’ injury from the impact.

To quantify the effect of graphene nanotubes, researchers from the University of Massachusetts – Amherst tested them against heated vaporised laser pulses, which acted like gunpowder. In tests, the laser pulses were used to fire a micrometre sized glass bullet into sheets of graphene, examples used 0 to 100 sheets of graphene, at 3km per second. This is three times the speed of a bullet fired from an M16 rifle, reported the AZoNano journal.

The graphene nanotubes absorbed the impact by stretching into a cone shape at the point of the bullet’s strike, and then cracking outwards. The evidence of cracks points to a weakness in the material, but it still outperformed Kevlar and absorbed 10 times more kinetic energy than steel.

Layering the graphene sheets is one proposal to resolve this weakness, another has to be the commercially viable mass production of graphene for the construction of the nanotubes.

In parallel to graphene research, the Florida Atlantic University has received a grant of over $500,000 from the Combating Terrorism Technical Support Office to develop fibres for body armour. It hopes to produce advances in the ballistic fibre properties, for greater energy absorption and dissipation using composite fibres. It announced that its “Hybridization of Ultrahigh Molecular Weight Polyethylene (UHMWPE) with Nylon and Carbon Nanotubes for Improved Ballistic Performance,” project will run for two years and focus on the mechanical properties of composite fibres, with experimental and computational approaches to investigate manufacturing, testing, and predicting the performance of the modified polyethylene fibre.

ENDS